Оглавление

Transition shock[edit]

Culture shock is a subcategory of a more universal construct called transition shock. Transition shock is a state of loss and disorientation predicated by a change in one’s familiar environment that requires adjustment. There are many symptoms of transition shock, including:

- Anger

- Boredom

- Compulsive eating/drinking/weight gain

- Desire for home and old friends

- Excessive concern over cleanliness

- Excessive sleep

- Feelings of helplessness and withdrawal

- Getting «stuck» on one thing

- Glazed stare

- Homesickness

- Hostility towards host nationals

- Impulsivity

- Irritability

- Mood swings

- Physiological stress reactions

- Stereotyping host nationals

- Suicidal or fatalistic thoughts

- Withdrawal

Способы преодоления[править | править код]

По мнению американского антрополога Ф. Бока, существуют четыре способа разрешения конфликта, возникающего при культурном шоке.

Первый способ можно назвать геттоизацией (от слова гетто). Он осуществляется в ситуациях, когда человек попадает в другое общество, но старается или оказывается вынужден (из-за незнания языка, вероисповедания или по каким-нибудь другим причинам) избегать всякого соприкосновения с чужой культурой. В этом случае он старается создать собственную культурную среду — окружение соотечественниками, отгораживаясь этим окружением от влияния инокультурной среды.

Второй способ разрешения конфликта культур — ассимиляция. В случае ассимиляции индивид, наоборот, полностью отказывается от своей культуры и стремится целиком усвоить необходимые для жизни культурные нормы другой культуры. Конечно, это не всегда удается. Причиной неудачи может быть либо недостаточная способность личности приспособиться к новой культуре, либо сопротивление культурной среды, членом которой он намерен стать.

Третий способ разрешения культурного конфликта — промежуточный, состоящий в культурном обмене и взаимодействии. Для того чтобы обмен приносил пользу и обогащал обе стороны, нужна открытость с обеих сторон, что в жизни встречается, к сожалению, крайне редко, особенно, если стороны изначально неравны. На самом деле результаты такого взаимодействия не всегда очевидны в самом начале. Они становятся видимыми и весомыми лишь по прошествии значительного времени.

Четвёртый способ — частичная ассимиляция, когда индивид жертвует своей культурой в пользу инокультурной среды частично, то есть в какой-то одной из сфер жизни: например, на работе руководствуется нормами и требованиями другой культуры, а в семье, в религиозной жизни — нормами своей традиционной культуры.

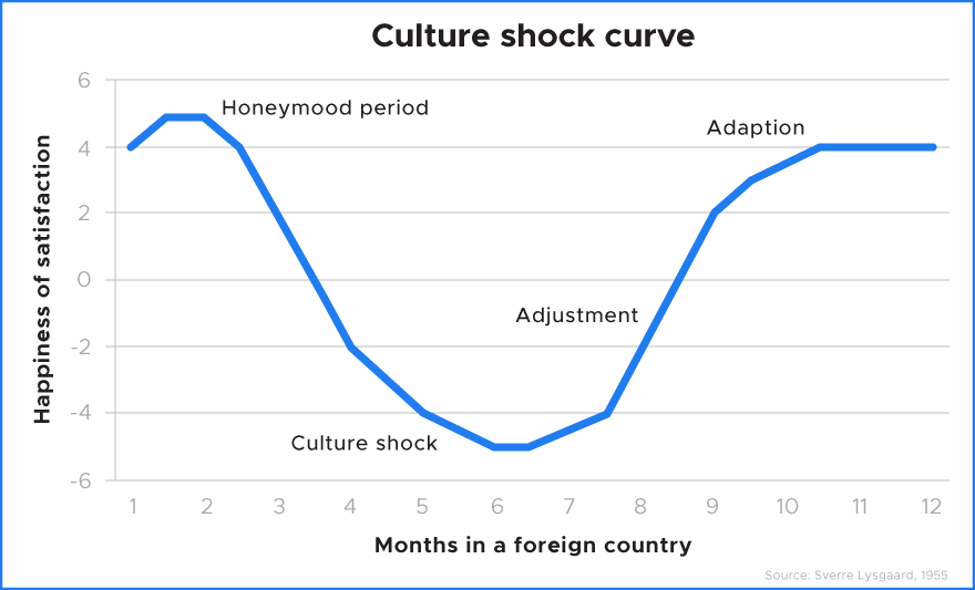

The 4 Stages of Culture Shock

People who experience culture shock may go through four phases that are explained below.

The Honeymoon Stage

The first stage is commonly referred to as the honeymoon phase. That’s because people are thrilled to be in their new environment. They often see it as an adventure. If someone is on a short stay, this initial excitement may define the entire experience. However, the honeymoon phase for those on a longer-term move eventually ends, even though people expect it to last.

The Frustration Stage

People may become increasingly irritated and disoriented as the initial glee of being in a new environment wears off. Fatigue may gradually set in, which can result from misunderstanding other people’s actions, conversations, and ways of doing things.

As a result, people can feel overwhelmed by a new culture at this stage, particularly if there is a language barrier. Local habits can also become increasingly challenging, and previously easy tasks can take longer to accomplish, leading to exhaustion.

Some of the symptoms of culture shock can include:

- Frustration

- Irritability

- Homesickness

- Depression

- Feeling lost and out of place

- Fatigue

The inability to effectively communicate—interpreting what others mean and making oneself understood—is usually the prime source of frustration. This stage can be the most difficult period of cultural adjustment as some people may feel the urge to withdraw.

For example, international students adjusting to life in the United States during study abroad programs can feel angry and anxious, leading to withdrawal from new friends. Some experience eating and sleeping disorders during this stage and may contemplate going home early.

The Adaptation Stage

The adaptation stage is often gradual as people feel more at home in their new surroundings. The feelings from the frustration stage begin to subside as people adjust to their new environment. Although they may still not understand certain cultural cues, people will become more familiar—at least to the point that interpreting them becomes much easier.

The Acceptance Stage

During the acceptance or recovery stage, people are better able to experience and enjoy their new home. Typically, beliefs and attitudes to their new surroundings improve, leading to increased self-confidence and a return of their sense of humor.

The obstacles and misunderstandings from the frustration stage have usually been resolved, allowing people to become more relaxed and happier. At this stage, most people experience growth and may change their old behaviors and adopt manners from their new culture.

During this stage, the new culture, beliefs, and attitudes may not be completely understood. Still, the realization may set in that complete understanding isn’t necessary to function and thrive in the new surroundings.

A specific event doesn’t cause culture shock. Instead, it can result from encountering different ways of doing things, being cut off from behavioral cues, having your own values brought into question, and feeling you don’t know the rules.

Концепция айсберг

Вероятно, одной из самых известных метафор описания «культурного шока» является концепция айсберга. Она подразумевает, что культура состоит не только из того, что мы видим и слышим (язык, изобразительное искусство, литература, архитектура, классическая музыка, поп-музыка, танцы, кухня, национальные костюмы и др.), но и из того, что лежит за пределами нашего первоначального восприятия (восприятие красоты, идеалы воспитания детей, отношение к старшим, понятие греха, справедливости, подходы к решению задач и проблемы, групповая работа, зрительный контакт, язык тела, мимика, восприятие себя, отношение к противоположному полу, взаимосвязь прошлого и будущего, управление временем, дистанция при общении, интонация голоса, скорость речи и др.)

Суть концепции заключается в том, что культуру можно представить в виде айсберга, где над поверхностью воды находится лишь небольшая видимая часть культуры, а под кромкой воды весомая невидимая часть, которая не оказывается в поле зрения, однако, оказывает большое влияние на наше восприятие культуры в целом. При столкновении в неизвестной, находящейся под водой частью айсберга (культуры) чаще всего и возникает культурный шок .

Американский исследователь Р. Уивер уподобляет культурный шок встрече двух айсбергов: именно «под водой», на уровне «неочевидного», происходит основное столкновение ценностей и менталитетов

Он утверждает, что при столкновении двух культурных айсбергов та часть культурного восприятия, которая прежде была бессознательной, выходит на уровень сознательного, и человек начинает с большим вниманием относиться как к своей, так и к чужой культуре. Индивид с удивлением осознаёт наличие этой скрытой системы контролирующих поведение норм и ценностей лишь тогда, когда попадает в ситуацию контакта с иной культурой. Результатом этого становится психологический, а нередко и физический дискомфорт — культурный шок .

Результатом этого становится психологический, а нередко и физический дискомфорт — культурный шок .

Outcomes[edit]

There are three basic outcomes of the adjustment phase:

- Some people find it impossible to accept the foreign culture and to integrate. They isolate themselves from the host country’s environment, which they come to perceive as hostile, withdraw into an (often mental) «ghetto» and see return to their own culture as the only way out. This group is sometimes known as «Rejectors» and describes approximately 60% of expatriates. These «Rejectors» also have the greatest problems re-integrating back home after return.

- Some people integrate fully and take on all parts of the host culture while losing their original identity. This is called cultural assimilation. They normally remain in the host country forever. This group is sometimes known as «Adopters» and describes approximately 10% of expatriates.

- Some people manage to adapt to the aspects of the host culture they see as positive, while keeping some of their own and creating their unique blend. They have no major problems returning home or relocating elsewhere. This group can be thought to be cosmopolitan. Approximately 30% of expats belong to this group.

Culture shock has many different effects, time spans, and degrees of severity. Many people are handicapped by its presence and do not recognize what is bothering them.[citation needed]

Culture Shock FAQs

What is the definition of culture shock?

Culture shock or adjustment occurs when someone is cut off from familiar surroundings and culture after moving or traveling to a new environment. Culture shock can lead to a flurry of emotions, including excitement, anxiety, confusion, and uncertainty.

Is culture shock good or bad?

Although it may have a seemingly negative connotation, culture shock is a normal experience that many people go through when moving or traveling. While it can be challenging, those who can resolve their feelings and adjust to their new environment often overcome culture shock. As a result, cultural adjustment can lead to personal growth and a favorable experience.

What is an example of culture shock?

For example, international students that have come to the United States for a study abroad semester can experience culture shock. Language barriers and unfamiliar customs can make it challenging to adjust, leading some students to feel angry and anxious. As a result, students can withdraw from social activities and experience minor health problems such as trouble sleeping.

Over time, students become more familiar with their new surroundings as they make new friends and learn social cues. The result can lead to growth and a new appreciation of the culture for the study abroad student as well as the friends from the host country as both learn about each other’s culture.

What are the types of culture shock?

Culture shock is typically divided into four stages: the honeymoon, frustration, adaptation, and acceptance stage. These periods are characterized by feelings of excitement, anger, homesickness, adjustment, and acceptance.

Возможные причины

Существует немало точек зрения, касающихся причин культурного шока. Так, исследователь К. Фурнем, на основе анализа литературных источников, выделяет восемь подходов к природе и особенностям данного явления, комментируя и показывая в некоторых случаях даже их несостоятельность:

- появление культурного шока связано с географическим перемещением, вызывающим реакцию, напоминающую оплакивание (выражение скорби по поводу) утраченных связей. Тем не менее, культурный шок не всегда связан с горем, поэтому в каждом отдельном случае невозможно предсказать тяжесть утраты и, соответственно, глубину этой скорби;

- вина за переживание культурного шока возлагается на фатализм, пессимизм, беспомощность и внешний локус контроля человека, попавшего в чужую культуру. Но это не объясняет различий в степени дистресса и противоречит предположению, что большинство «путешественников» (мигрантов) субъективно имеют внутренний локус контроля;

- культурный шок представляет собой процесс естественного отбора или выживания самых приспособленных, самых лучших. Но такое объяснение слишком упрощает присутствующие переменные, поскольку большинство исследований культурного шока не прогнозирующие, а ретроспективные;

- вина за возникновение культурного шока возлагается на ожидания приезжего, неуместные в новой обстановке. При этом не доказана связь между неудовлетворенными ожиданиями и плохим приспособлением;

- причиной культурного шока являются негативные события и нарушение ежедневного распорядка в целом. Однако измерить происходящие события и установить причинность очень сложно: с одной стороны, сами пострадавшие являются виновниками негативных событий, а с другой стороны, негативные события заставляют страдать этих людей;

- культурный шок вызывается расхождением ценностей из-за отсутствия взаимопонимания и сопутствующих этому процессу конфликтов. Но какие-то ценности более адаптивны, чем другие, поэтому ценностный конфликт сам по себе не может быть достаточным объяснением;

- культурный шок связан с дефицитом социальных навыков, вследствие чего социально неадекватные или неопытные люди переживают более трудный период приспособления. Тем не менее, здесь преуменьшается роль личности и социализации, а в таком понимании приспособления присутствует скрытый этноцентризм;

- вина возлагается на недостаток социальной поддержки, причем в данном подходе приводятся аргументы из теории привязанности, теории социальной сети и психотерапии. Однако достаточно сложно количественно измерить социальную поддержку или разработать механизм либо процедуру социальной поддержки, чтобы проверить и обосновать такое заключение .

В основном человек получает культурный шок, попадая в другую страну, отличающуюся от страны, где проживает, хотя и с подобными ощущениями может столкнуться и в собственной стране при внезапном изменении социальной среды.

У человека возникает конфликт старых и новых культурных норм и ориентаций, — старых, к которым он привык, и новых, характеризующих новое для него общество. Это конфликт двух культур на уровне собственного сознания. Культурный шок возникает, когда знакомые психологические факторы, которые помогали человеку приспосабливаться к обществу, исчезают, а вместо этого появляются неизвестные и непонятные, пришедшие из другой культурной среды.

Такой опыт новой культуры неприятен. В рамках собственной культуры создается стойкая иллюзия собственного видения мира, образа жизни, менталитета и т. п. как единственно возможного и, главное, единственно допустимого. Подавляющее количество людей не осознает себя как продукт отдельной культуры, даже в тех редких случаях, когда они понимают, что поведение представителей других культур собственно и определяется их культурой. Только выйдя за пределы своей культуры, то есть встретившись с другим мировоззрением, мироощущением и т. д., можно понять специфику своего общественного сознания, увидеть различие культур.

Люди по-разному переживают культурный шок, неодинаково осознают остроту его воздействия. Это зависит от их индивидуальных особенностей, степени сходства или несходства культур. К этому можно отнести целый ряд факторов, включая климат, одежду, еду, язык, религию, уровень образования, материальное благосостояние, структуру семьи, обычаи и т. д.

Oberg’s four phases model[edit]

According to acculturation model, people will initially have (1) honeymoon period, and then there will be (2) transition period, that is, cultural shock. This period may be marked by rejection of the new culture, as well as romanticizing one’s home culture. But then, with some time and perhaps help from local people or other culture brokers, people will start to (3) adapt (the dotted line depicted some people hated by new cultures instead). And (4) refers to some people returning to their own places and re-adapting to the old culture.

Kalervo Oberg first proposed his model of cultural adjustment in a talk to the Women’s Club of Rio de Janeiro in 1954.

Honeymoonedit

During this period, the differences between the old and new culture are seen in a romantic light. For example, in moving to a new country, an individual might love the new food, the pace of life, and the locals’ habits. During the first few weeks, most people are fascinated by the new culture. They associate with nationals who speak their language, and who are polite to the foreigners. Like most honeymoon periods, this stage eventually ends.

Negotiationedit

After some time (usually around three months, depending on the individual), differences between the old and new culture become apparent and may create anxiety. Excitement may eventually give way to unpleasant feelings of frustration and anger as one continues to experience unfavorable events that may be perceived as strange and offensive to one’s cultural attitude. Language barriers, stark differences in public hygiene, traffic safety, food accessibility and quality may heighten the sense of disconnection from the surroundings.

While being transferred into a different environment puts special pressure on communication skills, there are practical difficulties to overcome, such as circadian rhythm disruption that often leads to insomnia and daylight drowsiness; adaptation of gut flora to different bacteria levels and concentrations in food and water; difficulty in seeking treatment for illness, as medicines may have different names from the native country’s and the same active ingredients might be hard to recognize.

Still, the most important change in the period is communication: People adjusting to a new culture often feel lonely and homesick because they are not yet used to the new environment and meet people with whom they are not familiar every day. The language barrier may become a major obstacle in creating new relationships: special attention must be paid to one’s and others’ culture-specific body language signs, linguistic faux pas, conversation tone, linguistic nuances and customs, and false friends.

In the case of students studying abroad, some develop additional symptoms of loneliness that ultimately affect their lifestyles as a whole. Due to the strain of living in a different country without parental support, international students often feel anxious and feel more pressure while adjusting to new cultures—even more so when the cultural distances are wide, as patterns of logic and speech are different and a special emphasis is put on rhetoric.

Adjustmentedit

Again, after some time (usually 6 to 12 months), one grows accustomed to the new culture and develops routines. One knows what to expect in most situations and the host country no longer feels all that new. One becomes concerned with basic living again, and things become more «normal». One starts to develop problem-solving skills for dealing with the culture and begins to accept the culture’s ways with a positive attitude. The culture begins to make sense, and negative reactions and responses to the culture are reduced.

Adaptationedit

In the mastery stage individuals are able to participate fully and comfortably in the host culture. Mastery does not mean total conversion; people often keep many traits from their earlier culture, such as accents and languages. It is often referred to as the bicultural stage.

How to Overcome Culture Shock

Time and habit help deal with culture shock, but individuals can minimize the impact and speed the recovery from culture shock.

- Be open-minded and learn about the new country or culture to understand the reasons for cultural differences.

- Don’t indulge in thoughts of home, constantly comparing it to the new surroundings.

- Write a journal of your experience, including the positive aspects of the new culture.

- Don’t seal yourself off—be active and socialize with the locals.

- Be honest, in a judicious way, about feeling disoriented and confused. Ask for advice and help.

- Talk about and share your cultural background—communication runs both ways.

Stages and Examples of Culture Shock

Culture shock has many stages. Each one of these stages can be ongoing or only appear at certain times. We have listed the 5 stages of culture shock below. If you are a foreigner who is staying for a shorter period of time, you may just experience the first 2 to 3 stages of culture shock.

Stage 1 (the honeymoon stage)

In this first stage, the you may feel exhilarated and pleased by all of the new things encountered. The new things you encounter in your host country are new and exciting at first, everything is wonderful. Even the most simple things are new and interesting, taking the bus or going to a restaurant. This exhilarating feeling will probably at some point change to the next phase.

Stage 2 (the disillusionment stage)

Culture shock will happen gradually, and you may encounter some difficulties or simple differences in your daily routine. For example, communication problems such as not being understood, unusual foods, differing attitudes and customs; these things may start to irritate you. At this this stage you may have feelings of discontent, impatience, anger, sadness, and a feeling of incompetence.

This happens when you are trying to adapt to a new culture that is very different from your own. The change between your old methods and those of your host country/culture is a difficult process and takes time to complete. During the transition period, you may have some strong feelings of dissatisfaction and start to compare where you’re living to your home country in an unfavorable way.

Stage 3 (the understanding stage – enlightenment)

The third stage is characterized by gaining some understanding of Taiwan’s culture, country, and its’ people. You will get a new feeling of pleasure and sense of humor may be experienced. You should start to feel more of a certain psychological balance. During this stage you won’t feel as lost and should begin to have a feeling of direction. At this point you are more familiar with the environment and have more of a feeling of wanting to belong.

Stage 4 (the integration stage)

The fourth stage of culture shock is the integration stage and is usually experienced if you are staying for a very long period of time in in your host country. You will probably realize that the country has good and bad things to offer you. This integration is period is characterized by a strong feeling of belonging. You will start to define yourself and begin establishing goals.

Stage 5 (the re-entry stage)

The final stage of culture shock occurs when you return to your home country, often called reverse culture shock. This stage of culture shock generally only effects people who have been in a foreign country for a very long period of time (though many feel it after having lived overseas for only as little as 6 months).

You may find that things are no longer the same in your home country. For example, some of your newly acquired customs are not in use in your own country. Your friends have changed and your family may have as well. You may feel like you don’t fit in back home. Your driving habits have changed! These things will all contribute to an unusual feeling during your initial period of return.

These stages are present at different times and you will have your own way of reacting in each stage. As a result some you may find some stages can be longer and more difficult than others. There are many factors contribute to the duration and effects of culture shock. For example, your state of mental health, personality, previous experiences, socio-economic conditions, familiarity with the language, family, and level of education.

What is Culture Shock? – Causes

Culture Shock is caused by an anxiety when experiencing new unfamiliar surroundings. The different cultural cues like gestures, customs, idioms, language, beliefs etc. in you new surroundings and which are used in everyday situations and in communication with the locals have to be learnt and understood.

You feel like an outsider because you do not understand the facial expressions, traditions and routines of the locals for example. This however makes you aware of your own culture and upbringing. At home you knew how to behave and function in your own cultural settings.

Being transplanted into a new culture uproots all you know about getting around without creating any trouble or problems and everything you know and makes you feel safe. And then your familiar cultural cues have been taken away and you have to struggle to acquire a new set of cultural cues to regain that feeling of belonging.

Kalervo Oberg (1901-1973), world-renowned anthropologist, spoke about that reaction when moving and living abroad and he explained that there is a high dependence on these familiar clues, if they are not there we feel like “He or she is like a fish out of water. No matter how broad-minded or full of good you may be, a series of props have been knocked from under you, followed by a feeling of frustration and anxiety.”

Citation from: Kalervo Oberg: Culture Shock 1954 — read the full article in: www.smcm.edu/academics/internationaled/pdf/cultureshockarticle.pdf

Culture Shock Stages

Many researchers have written about culture shock and it is widely recognised that there are four different stages to the process – honeymoon, negotiation, adjustment and adaptation. Read on to find out more about each stage.

Source – Sverre Lysgaard, 1955

1. Honeymoon Stage

The Honeymoon Stage is the first stage of culture shock, and it can often last for several weeks or even months. This is the euphoric phase when you’re fascinated by all the exciting and different aspects of your new life – from the sights and smells to the pace of life and cultural habits.

During this phase, you’re quick to identify similarities between the new culture and your own, and you find the locals hospitable and friendly. You may even find things that would be a nuisance back home, such as a traffic jam, amusing and charming in your new location.

However, unfortunately, the honeymoon period must always come to an end.

2. Negotiation Stage

Next is the negotiation stage which is characterised by frustration and anxiety. This usually hits around the three-month mark, although it can be earlier for some individuals. As the excitement gradually disappears you are continually faced with difficulties or uncomfortable situations that may offend or make you feel disconnected.

The simplest of things may set you off. Maybe you can’t remember the way back to your new home because the street signs are confusing, or you can’t fathom how and what to order in a restaurant.

At this point, you also start to miss your friends and family back home and idealise the life you had there. This is often when physical symptoms can appear and you may experience minor health ailments as a result of the transition.

You may not find the locals so friendly anymore and you express feelings of confusion, discontent, sadness, and even anger.

3. Adjustment Stage

Thankfully this phase will come to an end as you begin to move into the adjustment phase, usually at around six to twelve months. This is the stage where life gradually starts to get better and routine sets in.

You begin to get your bearings and become more familiar with the local way of life, food and customs. By this point you may have made a few friends or learnt some of the languages, helping you to adjust and better understand the local culture.

You may still experience some difficulties at this stage, but you’re now able to handle them in a more rational and measured way.

4. Adaptation Stage

Finally, you reach the adaptation stage, sometimes know as the bicultural stage. You now feel comfortable in your new country and better integrated – you have successfully adapted to your new way of life.

You no longer feel isolated and lonely and are used to your new daily activities and friends. While you may never get back to the heightened euphoria you felt during the honeymoon stage, you’ve now gained a strong sense of belonging and finally feel at home in your new environment.

5. Re-entry Shock

It’s also important to note that there can be the fifth stage of this process. Re-entry or reverse culture shock can happen once you return home after living abroad for an extended period.

You may quickly realise that things are very different from when you left, and feel like you no longer belong as your family, friends and even your home town have changed and moved on without you.

You might find yourself saddened that your newly learned customs and tradition are not applicable in your home country, and you have to go through the whole process of adjustment and adaptation all over again!

Примечания[править | править код]

- Культурология и межкультурная коммуникация. — учебник для студентов. — Ростов-на-Дону: Феникс, 2007.

- Oberg K. Practical Anthropology. New Mexico, 1960.

- (недоступная ссылка). Дата обращения: 30 ноября 2016.

- (недоступная ссылка). Дата обращения: 30 ноября 2016.

- ↑

- Психологическая энциклопедия / под редакцией , . — СПб., 2006. — 1096 с.

- Садохин, А. П. Культурология. Теория культуры / А. П. Садохин, Т. Г. Грушевицкая. — М.: ЮНИТИ-ДАНА, 2004.

- Стефаненко Т.Г. Этнопсихология: учебник для вузов. – М.: Институт психологии РАН; «Академический проект», 1999.

- Bock Ph. K. (Ed.). Culture Shock. A Reader in Modern Cultural Anthropology. — N.Y., 1970.

Эта тема закрыта для публикации ответов.